Search

How the pandemic will aggravate multidimensional poverty in Afghanistan

A simulation exercise of the effects of COVID-19 in the South Asian country revealed socio-economic disruption and significant health threats for a population already suffering from food insecurity and lack of adequate sanitation. According to the analysis, the incidence of multidimensional poverty in Afghanistan could increase from 51.7% to 73.5%.

Expanding access to clean water sources as part of the health response, as well as improving the infrastructure and the supply of basic services, are some of the urgent actions needed in Afghanistan to address the COVID-19 pandemic in a country where multidimensional poverty afflicts more than half of its population.

This is one of the recommendations of the analysis of the virus’ impact on multidimensional poverty in Afghanistan, conducted by the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI), University of Oxford and UNICEF in Afghanistan. Using data from the Afghanistan Living Conditions Survey 2016/17, the researchers performed two types of analyses. In the first of these, based on Afghanistan’s Multidimensional Poverty Index (see box), they analysed the population’s levels of vulnerability in order to describe the potential immediate health threat of the pandemic. The second analysis, using micro-simulations, examined the socio-economic disruptions generated by the necessary response measures to reduce the rate of infection.

In relation to the health threats from COVID-19, it is important to observe that the reality of Afghanistan presents alarming baseline conditions that make the spread of the virus more worrying, such as food insecurity, lack of adequate sanitation, lack of a safe source of drinking water and lack of access to clean cooking fuel.

Thus, 8 out of 10 adults in the country face at least one of those deprivations. Only in Kabul Province is the situation somewhat better than in most other provinces – 5 out of 10 people live with at least one predisposing factor – while in most other provinces, it is 8 and 9 out of 10 people.

But the most alarming situation is experienced by the children of Afghanistan, where 9 out of 10 face at least one of these deprivations, and, on average, children aged 0–17 bear the highest burden in all predisposing factors individually, compared to all other population subgroups.

The majority of the population at risk is multidimensionally poor, although, again, as a proportion, children bear the greatest burden.

Subnational disparities are more visible in terms of high risk for COVID-19. In Kabul, 1 in 1,000 people is at high risk for COVID-19, but more than 1 in 4 people face this situation in Badghis, Daykundi, Ghor, and Sar-e-Pul. This is also the case for more than 3 in 10 people in Nooristan and, worryingly, for 4 and 5 in 10 people in Urozgan and Samangan, respectively.

Socio-economic disruptions

75.5% of Afghanistan’s population lives in households where all working members are in vulnerable employment, which is characterised by informal work arrangements and insecure tenure. These jobs are unstable, with inadequate income, low productivity, and a lack of safety nets.

These workers have no protection against loss of income in times of economic hardship. Being key members of their families, these people are part of the population that may be most at risk of suffering the negative socio-economic disruptions generated by COVID-19.

The majority of the population at risk is multidimensionally poor, although, again, as a proportion, children bear the greatest burden.

Moreover, if simultaneous work deprivations persist in the form of unemployment, the effect of young people not in education, employment or training (NEETs), plus a high dependency rate (less than 1 household member working for every 6 people), the incidence of multidimensional poverty in Afghanistan could increase from 51.7% to 73.5%.

Furthermore, about 11.9 million people could be deprived in food security. If these people cannot return to a non-deprivation situation, the incidence of multidimensional poverty could increase by 10 percentage points, from 51.7% to 61.4%.

Children are not spared in this respect, either. It is estimated that between the ages of 6 and 18, deprivation in school attendance could increase from 5.6 million to 9.7 million. This is not insignificant: if these children cannot return to school, the incidence of multidimensional poverty could increase up to 60.9 %.

Recommendations

Given the high incidence of multidimensional poverty in Afghanistan, the authors of this report formulated health and socio-economic recommendations, after simulating five scenarios representing different dynamics of deteriorating well-being. Each of these scenarios involves assigning random identifiers to carefully selected population subgroups, and then triggering simulated deprivation in the relevant indicators. This procedure was applied in each province to capture particular effects, This procedure was applied in each province and at the national level.

Among the main recommendations, we can highlight that they consider that “it is important to expand water services as part of the sanitation response. These services should aim to provide the opportunity for people to constantly wash their hands and prevent infection”. To implement this, “the central government must consider important heterogeneities at the provincial level, and plan specific strategies, given the resources of each region. It is also necessary to design and implement close and timely actions, coordinated between central and local governments”.

“In combination with these preventive emergency policies, it is necessary to ensure that quarantine and social distancing policies are effective, as they protect people from falling into multidimensional poverty,” they stress.

To ensure effectiveness, the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI), University of Oxford and UNICEF Afghanistan believe “it is necessary to consider social protection measures, including cash grants, throughout the whole quarantine period to safeguard the general welfare of the affected population”, since “multidimensional poverty could rise if children do not return to school; or if people face food insecurity on a regular basis; and if many already very vulnerable workers experience further deterioration of their working conditions”.

________________________________________________________________

Afganistan-MPI

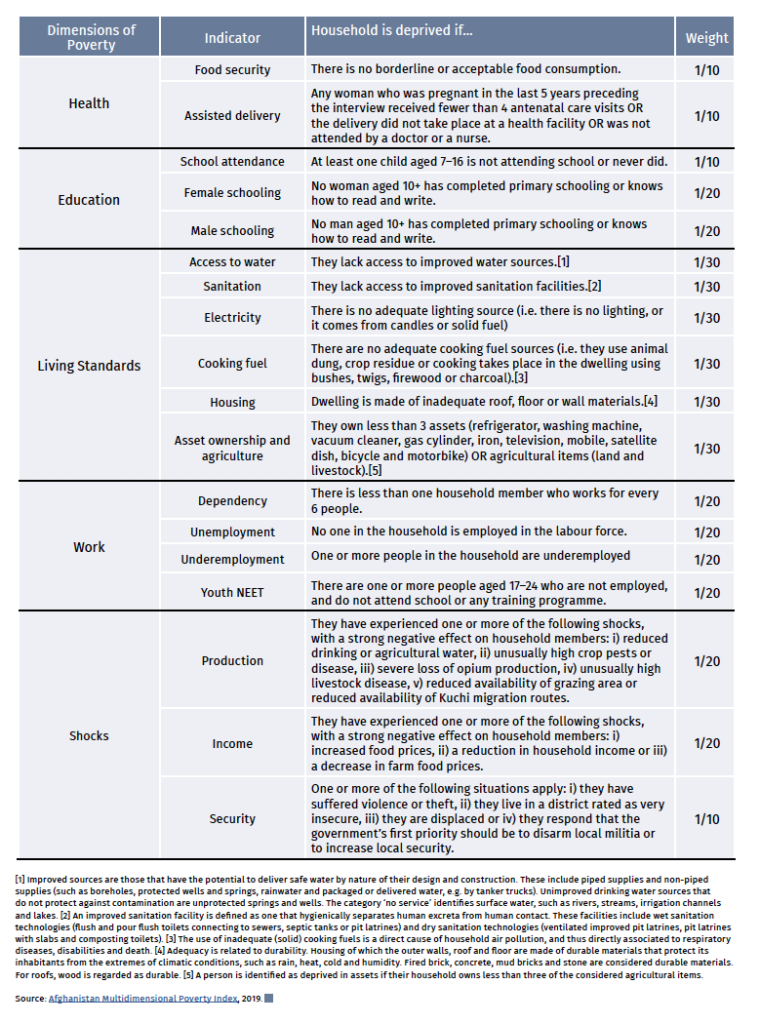

The Afghanistan Multidimensional Poverty Index (AF-MPI) was launched on March 31, 2019 with the aim of measuring multidimensional poverty in the country and providing key information for the creation of effective public policies.

The AF-MPI is calculated using the Afghanistan Living Conditions Survey and consists of five dimensions and 18 indicators that were selected in a consultation process with the country’s top-level policy makers and technical experts. A person is identified as poor if they are deprived in at least 40% or more of the dimensions or weighted indicators.

This article was published in Dimensions 10.