Search

Rebooting the Global MPI

The year 2018 turned out to be one of the most demanding yet stimulating years for the OPHI team. One key achievement for the team was the collective effort in revising the global Multidimensional Poverty Index or MPI – an internationally comparable measure of acute poverty for developing countries. The motivation for the revision was the progress made in terms of data availability for measuring human development in the last decade. For this, we must acknowledge the outstanding work carried out by global micro-data providers such as the Demographic Health Survey (DHS) team and the Multiple Indicators Cluster Survey (MICS) team.

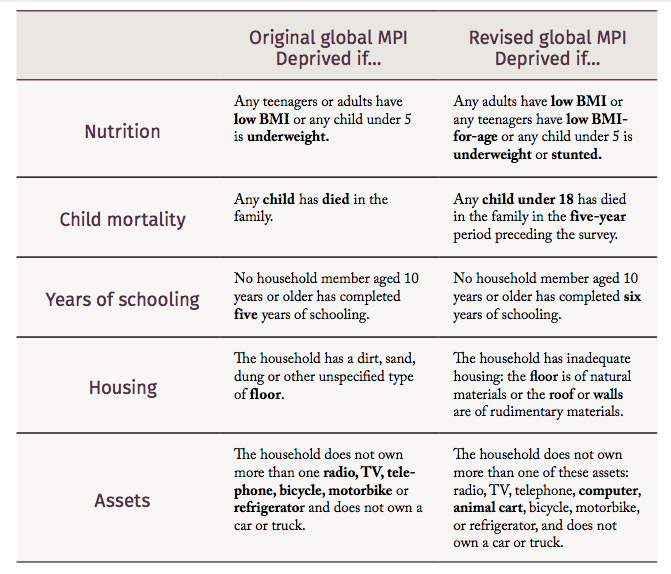

A key highlight of the global MPI is its ability to measure and capture the simultaneous deprivations experienced by each person across ten indicators that relate to the three major dimensions of human development: health, education, and living standards. The number of people who experience multidimensional poverty is obtained by identifying those who are deprived in at least one-third of the ten weighted indicators. In general, the Alkire-Foster methodology of the index has remained the same – three dimensions, ten indicators and one-third as the poverty cut-off. The 2018 revision specifically focused on the indicators, five of them were updated (summarized in the table below).

The child nutrition indicator was the most challenging in terms of reaching a consensus. The revision of this indicator meant re-opening the debate on what indicator best captures the nutritional status of a child: stunting (height-for-age), underweight (weight-for-age), and/or wasting (weight-for-height). The original global MPI only took into account the children’s underweight indicator. Consultations with data providers and nutrition experts resulted in the decision to identify any child under five as deprived if the he or she was underweight and/or stunted.

In half of the countries covered by the global MPI, anthropometric data was also collected from teenagers and adults aged 15 to 49 years – and even older than 49 years in a handful of them. In these countries, the nutrition indicator was based on the underweight measure for children under five and the body mass index (BMI) measure for all individuals aged 15 years and older. However, the BMI measure is considered less accurate for teenagers, given their sporadic growth. A lanky 16 year-old may be skinny, hence identified as deprived by the BMI measure, but this is a natural physiological phenomenon experienced by those in the age group and hence is less likely to be identified as deprived by a BMI measure that is adjusted by age. As a result, the revised nutrition indicator applies the BMI-for-age measure for teenagers (15–19 years) and the BMI measure for adults 20 years and older. The decision on teenager and adult nutrition was straightforward as the literature on the BMI measure and expert opinions were less divergent.

The revised global MPI launched by UNDP and OPHI on 20 September 2018 is a shared achievement.

Another demanding and thought-provoking debate was centred on the revision of the child mortality indicator, with one particular question hitting us hard: whether a family who experienced child mortality ten years back is less affected emotionally and financially than a family who lost a child more recently. Previously, the index took into account any reported child death, that is, without any time condition. The revised indicator takes into account the deaths reported in the five years preceding the survey. The decision to set a time condition was reached based on policy relevance. There is a stronger policy incentive to focus on more recent deaths among children than on deaths that occurred further in the past. The policy relevance argument was further strengthened in 2019, when an age cut-off was also introduced. Individuals will now be identified as deprived in the child mortality indicator if they live in a household where there is any incident of death among children under 18 in the five years preceding the survey.

Our easiest revision was related to the years of schooling indicator. Previously, a household was identified as deprived if no member had completed at least five years of formal education. This was revised to six years of education, which, in the majority of the countries analysed with the global MPI conforms to the completion of primary level schooling.

One of the revisions that we looked forward to implementing was the housing indicator. Since 2016, we had recognized a significant improvement in the availability of data related to this indicator. This includes the availability of information on materials used to construct the walls, roof and floor of a household. The combination of this information meant that we can now assess the habitable condition of the houses inhabited by people around the world.

In our earlier work, we identified individuals as deprived if they were living in households that had no floor or if the floor was constructed from dung or dirt. In the revised index, in addition to considering flooring materials, individuals are also identified as deprived if their dwelling has no roof or walls, or if the roof or walls were constructed using natural or rudimentary materials such as carton and plastic.

The fifth indicator that was revised, and unquestionably went through the longest process of revision, was the assets indicator. Previously, the aggregated assets indicator identified ownership of a car and six small items, namely, a television, radio, telephone, refrigerator, bicycle and motorbike. Households that owned a car were automatically identified as non-deprived. Individuals were identified as deprived if they lived in households that had only one or none of the small assets.

After a substantial number of analyses and engagement with the literature, the revised version of the aggregated assets indicator included two additional small items: a computer and animal cart. The former reflects global technological growth, while the latter reflects the ease of the mobility of people and goods in rural communities. The identification of who is deprived in assets remained the same despite the increase in small assets from six in the previous round to eight items in the current round.

Change is never easy. Opening the debate on crucial questions related to nutrition, child mortality and assets meant that it was possible that this debate could go on and not reach a conclusive consensus. An in depth exploration of the indicators that best capture acute poverty is a valid exercise. However, the exercise must not come to a point where the global identification and estimation of multidimensional poverty is paused while we focus on achieving a consensus.

Some tough decisions were taken, but, more importantly, we were transparent about the changes and decisions made in the revised global MPI. We walked quite a distance in 2018 in terms of workload. This was only possible because of the enormous strength and support from team members and associates across the globe. The revised global MPI launched by UNDP and OPHI on 20 September 2018 is a shared achievement.

This article was published in Dimensions Magazine 6 (PDF).